Explore Christianity

Here you will find inspiring stories of faith, including my own, and answers to some of the questions that people might have about Christianity. I encourage you to spend time watching and reading the content and being proactive in exploring the life-transforming truths of the gospel.

My short book Making the Connection explains the message of Christianity and I would love you to read it for free here. Alternatively, you may want to watch my talk The Invitation which explains the offer being made to us today.

Grace and peace

J.John

I became a follower of Jesus when I was a student in London in 1975. My friend Andy had spent about six months explaining things to me, helping me to understand the Bible and helping me to understand how I could connect with Jesus. On 9th February, he showed me a little passage in the book of Revelation. It says:

Look! I stand at the door and knock. If you hear my voice and open the door, I will come in, and we will share a meal together as friends. (Revelation 3:20 NLT)

For me, that was my epiphany. I understood the concept. I basically said, ‘Jesus, I want you to come into my life.’ My mind was illuminated, and my heart was warmed. That was the beginning of my journey of following Jesus and knowing him personally.

My prayer is that you too will make the connection with Jesus and experience what I’ve experienced: forgiveness from the past, new life today and a hope for the future.

My journey of faith

Here is the story of my journey of faith, from making a commitment to Jesus in 1975 to preaching globally, I hope it inspires you to make the same decision.

My journey of faith

Here is the story of my journey of faith, from making a commitment to Jesus in 1975 to preaching globally, I hope it inspires you to make the same decision.

Faith stories

The stories below are from people who moved from living life one way to discovering the life-changing message of Jesus. Whatever your story, you too can come to Jesus today.

Questions about faith

Longer answers to important questions

The problem of evil and suffering is the big argument against Christianity. Whether suffering involves sick babies, grieving mothers or crippling injuries, it raises the most serious of questions. Why does a good and all-powerful God allow evil? Why doesn’t he just simply end that disease, heal that suffering child, stop that motorbike accident? Let me be as honest and specific as possible: why did God allow millions of people to die in the Nazi concentration camps when the simple act of giving Hitler a much-merited heart attack could have ended it all?

Right at the start it’s vital to recognise that this is a problem that people only really seriously raise with Christians. The reason for this is that we claim not only that there is an all-powerful God but that he is a loving God. In fact, a better version of the question we are examining would be why does a wise and loving God allow evil? You could understand the existence of evil if God wasn’t entirely in control of the universe or if there were several different gods battling it out amongst themselves. Equally, evil would be unsurprising if there was a God who was cruel or merely apathetic about the world. It’s only if, as Christians claim, you have a God who is all-wise, all-powerful and loving that we have this question.

In fact, to turn the question on its head it’s important to note that, if you are an atheist, strictly speaking there isn’t a problem of evil at all. Why not? Quite simply because ‘evil’ doesn’t exist: it’s just the way the world works. Don’t take my word for it. Take that of atheist Richard Dawkins who has written that in the universe there is ‘no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but pitiless indifference’. This raises the question for the atheist as to why everybody recognises evil exists and is shocked by it, when according to atheism evil doesn’t exist.

In considering a world in which wars, premature deaths, plagues, starvation and violence occur, Christians have come up with different responses to the problem of why these things occur. Let me summarise five of them.

Reason 1: Evil is a result of the world’s rebellion against God

The Bible is very clear that this world is not how God intended it to be. It is a rebellious planet and from the start human beings have chosen to disobey God’s commands. The result of this is a twisted or ‘fallen’ creation that we must live with. Disobedience has a price and much – but not all – evil is due to human rebelliousness or, to use a shorter word, sin. Whether you agree with that or not it is undeniable that if the world was a fairer, wiser and kinder place, many of the effects of natural disasters and diseases would be reduced. Flooding becomes worse because greed has allowed building in vulnerable places; earthquakes kill more people because poverty has resulted in poorly built houses; diseases spread further because vaccination programmes have been rejected or are unaffordable.

Reason 2: God can use evil to demonstrate goodness

Someone might praise the love that a young, healthy couple show for each other on the day of their marriage. Great! But let’s fast forward forty years when wrinkles, arthritis, baldness, fat and a host of ailments have taken hold. Yet they still love each other: so isn’t this battered but enduring love now even more praiseworthy? It’s hard to imagine the meaning of words such as courage, loyalty and sacrifice except where there has been some sort of struggle against evil. Light shines brightest in darkness, kindness stands out best in the face of cruelty and truth is most praiseworthy in a time of lies.

Reason 3: God can use bad things for our good

The Bible tells us that God is not content with his children as we are. He is constantly at work to change those who take the name of Christ in order to make them more and more like him. Unfortunately, we are all disinclined to change and sometimes gentle persuasion is not enough. When you are trying to free some fixed object in the house it’s not uncommon to give up using a small tool and, as a last resort, reach instead for the hammer and apply brute force. That principle applies to our lives. Sometimes, in order to produce change God needs to resort to allowing pain and suffering.

Experience tells us that it’s easy to remain arrogant and to reject God until something really unpleasant happens to us: only then do we treat him seriously. Hebrews 12 in the Bible talks about how God uses hardship as a tool of discipline to make his people what he wants them to be. Children cling more closely to their parents in the dark; God’s children cling closer to him when they are suffering.

Reason 4: Evil reminds us that this world is not our home

Imagine that you were living a prosperous life, free from all aches and pains in some comfortable part of the world. It would be lovely, but you might be tempted to think that you were already in paradise and that is a very dangerous state of mind. Life for the Christian is like travelling on a long plane journey where you break your journey on route or change planes at another airport. However tired you are, you have to remind yourself at this point that you’re not there yet: this is merely a temporary stopover. So it is with life. Evil and pain remind us (and we need reminding) that we have not yet arrived at our destination and that we need to keep pressing on until Jesus himself tells us that it’s all over. We are not home yet.

Reason 5: We only see a tiny part of the story

‘Why does God allow evil?’ is actually an inadequate question and what we really ought to do is rewrite it to ask, ‘Why does God allow evil in this life?’ From a Christian point of view, we need to think in terms of eternity: of time stretching on without end. To do that is to realise that what happens here in this life is utterly trivial compared to the years of eternity. Even if we were to have a life full of pain, it would still count as insignificant against knowing and enjoying God in paradise forever.

If Jesus was indeed more than a man and, in some way, God, then he becomes supremely important. He is alive, he knows who we are, what we are doing, what we are thinking and what our future is. As God he has authority to forgive, to heal and to rescue. He is someone who can be trusted completely in every situation, whatever life (and death) brings us.

Precisely because the idea that Jesus is God is of such overwhelming importance it has often been challenged. To be honest, many people are happier with a Jesus who is a long-dead prophet than a Jesus who is alive and all-powerful. Yet for nearly 2,000 years, mainstream Christianity has – against innumerable attacks – held firmly to the belief that Jesus is someone whom we can know as God.

One common means of trying to undermine the deity of Jesus is to assume that over the years his reputation grew because of some kind of ‘wishful thinking’. So, the theory goes, Jesus was originally no more than some sort of prophet but, with the passage of time, his followers ‘promoted’ him from being ‘a man who was good’ to ‘the man who was God’. History, however, will not allow us this option. For instance, we find extraordinary statements about Jesus in the letters of the New Testament where language that Jews would have used only for God is applied, without hesitation or qualification, to Jesus. He is ‘Lord’, he rules over everything, he is in heaven, he can be worshipped and prayed to. Some of these letters can be confidently dated within twenty years of the events of the first Easter. Outside the New Testament, we have a letter written in AD 112 by Pliny the Elder, a governor in what is now Turkey, to the Roman Emperor Trajan which mentions that Christians were ‘worshipping Christ as God’.

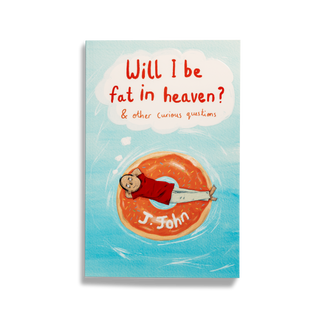

The divinity of Jesus was not accepted without careful thought. For several hundred years church leaders carefully thought about what this claim meant and how, if Jesus was considered to be God, God could still be one. The answer they came up with is the Trinity: something that I have discussed in my book Will I Be Fat in Heaven? And Other Curious Questions.

So why did so many devout Jewish people, upholders of a faith in which linking anything with God was blasphemy, consider that Jesus could be treated as God? The answer is found in the gospels, where we read about what Jesus of Nazareth said and did. In the book Jesus Christ – The Truth that Chris Walley and I wrote, we discuss not only the strong evidence for the authenticity of the gospels but also the identity of Jesus. Let me summarise here just some of the evidence for Jesus being God.

Jesus accepted titles that were only used of God. He frequently referred to himself as the ‘Son of God’, as ‘the Son of Man’ (a term with implications of being divine) and as the eternal ‘I am’. The angry reaction that his use of some of these terms produced indicates they were considered blasphemous.

- Jesus made claims and acted in a way that implied he was, in some way, God. So, for example, he declared that he personally was making a new covenant between God and the human race. He claimed to forgive people, to have existed in the past, to have authority over the temple, the Kingdom and God’s Law. Perhaps most remarkably, Jesus stated that, at the end of time, he personally would judge the world.

- Jesus claimed unity with God, saying, ‘Anyone who has seen me has seen the Father’ (John 14:9–10 NIV).

- Jesus performed miraculous actions that only God could do. He stilled storms, walked on water, exorcised demons, accomplished extraordinary healings and multiplied food. Particularly striking is the fact that nowhere in performing these deeds is there any reference to Jesus praying to God to ask him to do them. With an extraordinary personal authority, Jesus just did them himself.

- Whenever the Old Testament talks of prophets and what they preached we read the lines of ‘the Word of the Lord came to X’ or how prophet Y began his message with such words as ‘God says’. The message of the prophets is always, as it were, ‘second-hand’. Yet we never read anything like this of Jesus: he just says ‘I say’ or ‘truly I tell you’. Indeed, at the start of John’s gospel we are told that Jesus personally is the Word of God.

It is true that in the gospels Jesus only rarely makes an open claim to be God. This is in fact part of a pattern in which Jesus at first avoids directly stating that he is God but instead increasingly does and says things which, to those who are thinking about what is happening, present unmistakable but indirect claims to be God. Finally, at his trial Jesus is open in his claims to be God. Indeed, after the resurrection Jesus openly accepts worship (John 20:28).

There is one other argument about the divinity of Jesus that is often overlooked. Almost no historian, whether Christian or not, doubts that Jesus was crucified, apparently at the request of the religious leaders. Why did he arouse such hostility? We read of no comparable hatred against John the Baptist, who preached against the religious authorities in the strongest possible terms. The reason that Jesus was crucified was because the leaders believed that he had committed blasphemy for which death was the required punishment.

Finally, can I point out that whether or not Jesus was God is the ultimate in decisive questions. If Jesus claimed to be God but wasn’t, then he was either deranged or a deceiver and so nothing he said can be trusted. If, on the other hand, as Christians have always believed, Jesus not only claimed to be God but was God then every human quest for ultimate meaning ends with him. Jesus is all we need to know God. But if we do come to the verdict that Jesus is indeed God, the question now shifts from him to us. What are we going to do about Jesus?

There’s something incredibly attractive about the idea of a second opportunity; the possibility of, after having messed up an exam or an interview, being able to do it all over again. I imagine a good many of us would be walking or cycling to work if there had been no second (or third, fourth or fifth) opportunity on the driving test.

But what about life? Is there some post-mortem way of making up for our flawed lives with the wrong deeds that we have committed and good deeds we omitted? Now I am not referring to how God deals with those people who have never heard about Jesus and whether he offers them forgiveness and on what basis. No one knows what will happen to those who have never heard about that invitation, except we may be sure that it will involve Jesus and will be based on God’s great principles of justice and mercy.

The idea of a ‘second opportunity’ I want to talk about applies to those who, despite having heard about Christ in this life, have deliberately chosen to reject him. They have rejected God’s offer of forgiveness and have decided that, rather than accept Jesus as Saviour and Lord, they would rather run their lives on the all-too-common desire of ‘I’m going to do it my way’.

Actually, it’s difficult to know what people mean by ‘a second opportunity’. I suspect that most people imagine it as operating on the same principle as those courses on the perils of speeding that you get offered to avoid points on your driving licence when you have been caught over the speed limit. It seems to be imagined that, after a few years of, at best, mild discomfort and, at worst, tolerable torment, your penalty points are lifted and, with your record wiped clean of offences, you are finally allowed access to heaven.

Well, while there are attractions to this idea of a second opportunity, I can’t support it for several reasons. The first is because it flies in the face of what we know of how God saves people. If you believe that men and women are made right with God by ‘doing good things’, then I suppose it’s possible to imagine that a few years of enduring some kind of punishment might make up for a misspent earthly life. But that is not how ‘getting to heaven’ works.

The only way any human being will ever be in heaven will be because Jesus died for them on the cross. Doing good things, in this life or the next, will not help anybody because the only way of being saved is to trust in Christ and accept him as the one who paid the price for our sins on the cross. If you want to go to heaven you have to go via King’s Cross! That step of faith allows us to become new people, permanently cleansed from sin by Jesus. As the New Testament claims, ‘the blood of Jesus, his Son, purifies us from all sin’ (1 John 1:7 NIV). I don’t see how any sort of ‘second opportunity’ involving individuals somehow paying off their own moral debts fits with this.

The second reason that the idea of a ‘second opportunity’ is not something to hope for, is that there is no Bible evidence for it. The New Testament letter to the Hebrews is as clear as it can be: ‘Just as people are destined to die once, and after that to face judgement . . .’ (Hebrews 9:27 NIV).

Wherever the Bible talks about the future after death, it sees it simply in terms of heaven and hell. In the New Testament there is no hint of any kind of halfway house that would allow for a delayed entrance into heaven after an appropriate course of ‘therapy’. The New Testament is consistent: the life we are living now – and this life only – is where we are either saved or lost for all eternity. Furthermore, nothing in the history of the early church indicates that they thought a second opportunity was possible. The urgency with which the first Christians surged around the Mediterranean telling everybody they could find to put their faith in Jesus, suggests no one had told them about a second opportunity.

A third reason is that I find this ‘second opportunity’ idea psychologically problematic. If someone has rejected Christ in this life it’s difficult to see how a second opportunity is going to make much difference. With age, opinions become less fluid and more fixed. There’s an old English saying based on Ecclesiastes 11:3 that runs like this:

As a tree falls, so shall it lie;

As a man lives, so shall he die;

As a man dies, so shall he be;

Through all the eons of eternity.

Finally, as an evangelist I have to say that I have my own reasons for rejecting this idea of a second opportunity. It removes the need to make a decision for Jesus because there is the idea that we can make it up after death. It also removes the urgency in making a decision for Jesus. It was a helpful image of older preachers that there was a ‘gospel train’ standing before you that you either caught or missed. To believe in a second opportunity is to stand on the platform with the gospel train carriage doors open wide before you and to step back from it saying, ‘Actually, I think I’m going to wait for the next train.’ Let me be honest: everything I know tells me that to do this is a terrible mistake. There is no ‘next train’.

The account of the thief on the cross (Luke 23:39–43) is very encouraging. Here, in the last hours of his life, we see a very bad man finding forgiveness from Jesus and being promised immediate access to heaven. Deathbed conversions do occur but please don’t leave it till then. There are some things in life too important to risk and eternity is most definitely one of them. Don’t rely on a second opportunity. When it comes to the next life, this life is the only life that counts.

In a sense this is one of the most important questions that we have raised so far. Certainly, if you are not yet a Christian but believe that God exists, it is probably something that you’re concerned about. Actually, it’s a question in two parts: firstly, does God care? Secondly, does he care for me?

The caring bit about God is very important. You see, it’s relatively easy to believe in a God who is all-powerful, all-knowing and all-wise: a wonderful being so great and glorious that he can make a giraffe and manage a galaxy. Yet such a God could exist but be a cold and impersonal being: the Universe’s Chief Executive, far too preoccupied to care for us.

The Bible’s picture of God is very different and it repeatedly refers to him as someone who cares and indeed loves all he has made. In the Old Testament one of the great definitions of God is found in Exodus 34:6–7 (NIV) where we read that God ‘passed in front of Moses, proclaiming, “The Lord, the Lord, the compassionate and gracious God, slow to anger, abounding in love and faithfulness, maintaining love to thousands, and forgiving wickedness, rebellion and sin.”’

When we read the long history of the Old Testament, we see an enormous amount of evidence that God cares. He makes covenants with people, answers prayer and rescues individuals (and nations) from disaster. The stories of the Old Testament are full of individuals such as Moses, Joshua, Ruth, David and Esther, and they tell us how God dealt personally with them. That language of care and covenant love used in the Old Testament becomes stronger and richer in the New Testament where we read repeatedly of God’s love to men and women.

Yet in the New Testament we see these great Old Testament expressions of God’s love suddenly change into something dramatically different and infinitely richer. God’s care now goes beyond offering words, actions and faint glimpses of himself to a dramatic, personal intervention. Extraordinarily, beyond all comprehension, God himself comes to us as a human being – Jesus of Nazareth – and if that were not enough, goes to the cross and suffers there. The life and death of Jesus means many things but one thing it declares loudly is that God loves us to an extraordinary degree. It is as if God looks at the tragic, turbulent mess that is this world, recognises that no amount of religious teaching is going to save it and instead steps in to intervene personally. The cross proclaims that God loves each one of us enough to die for us.

OK, God cares, but you may have a reservation: does he care for me personally? After all, you might say, what reason is there for this great God to be particularly bothered about little me? I am an ordinary person, with ordinary concerns, in a world of around eight billion people.

I understand the concern but let me turn this on its head for you with a question. Why wouldn’t God be concerned for you? The Bible teaches how God reached out to all sorts of people, from all sorts of backgrounds. Indeed, if there is any bias in who God accepts, it seems to be towards the weak, the insignificant, the ordinary and the unlikely. Jesus pointed out that it was those who knew they were sinful who responded better to him than those who thought they were good. God welcomes all who turn to him in repentance, trusting in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ to save them. No one is too insignificant or too bad for God.

If you want further reassurance, just look at the two thousand years of Christian history. It’s full of stories of individuals who, having recognised that their lives were a mess and heard that Jesus Christ offered them a new life, have turned to him and had all that they were completely transformed.

Does God care for you? Yes, he does. There’s a verse in a psalm that is, in effect, an offer from God: ‘Taste and see that the Lord is good; blessed is the one who takes refuge in him’ (Psalm 34:8 NIV). Does God care for you? Yes, he does and I encourage you to receive him and know him.

Books to explore faith

You may find one or two of these books helpful as you explore faith in Jesus

The big question

Jesus offers us forgiveness from the past, new life today, and a hope for the future.

If you want to commit to following Jesus or commit to finding out more about Christianity, please click to watch a short video from J.John.

Get connected

If you would like help to get connected to a local church in your area, please click the button below and we will do our best to help connect you.